It’s been such a busy year for me. I went through the painstaking job application (perhaps worth a post in the future) in January, helped my family to recover from COVID in April, worked on a grant proposal in July, took care of my family during a medical issue in August, shipped my household from Israel to the States in September, vacated my apartment in Tel Aviv and visited the Weizmann Institute of Science until October, attended a workshop at CERN before traveling with Julie and Purr Purr (the cat) to New Mexico, settling and starting my new job in November, all this time making real progress on my projects with collaborators in five different time zones as well as fulfilling my community commitments like Snowmass white papers and serving as a referee for four journals. I guess I can definitely use some downtime to unwind during the holiday break. As I’m sure many of you also went through a lot this year, I wish you can find your peace during the holiday break.

Let’s think of something lighthearted, because, why not – the world is crazy enough with COVID and the war as well as the increasing tension in geopolitics and clash of ideologies – well I’m digressing.

When I was a kid, I used to wonder how physicists’ intuition navigates their research directions. More concretely, there are gazillion different things you can research and even more theories you can propose, how do you make sure you end up with the “right” one? The short answer is that you can’t, even for us professionals. Yet, the longer version is slightly less dismissive: you can’t be sure but there are tricks to help you quickly draw some intuition before investing a ton of your time into an idea, such are techniques to make sure that at least you don’t land too far from the truth. One of them is called the order-of-magnitude estimate.

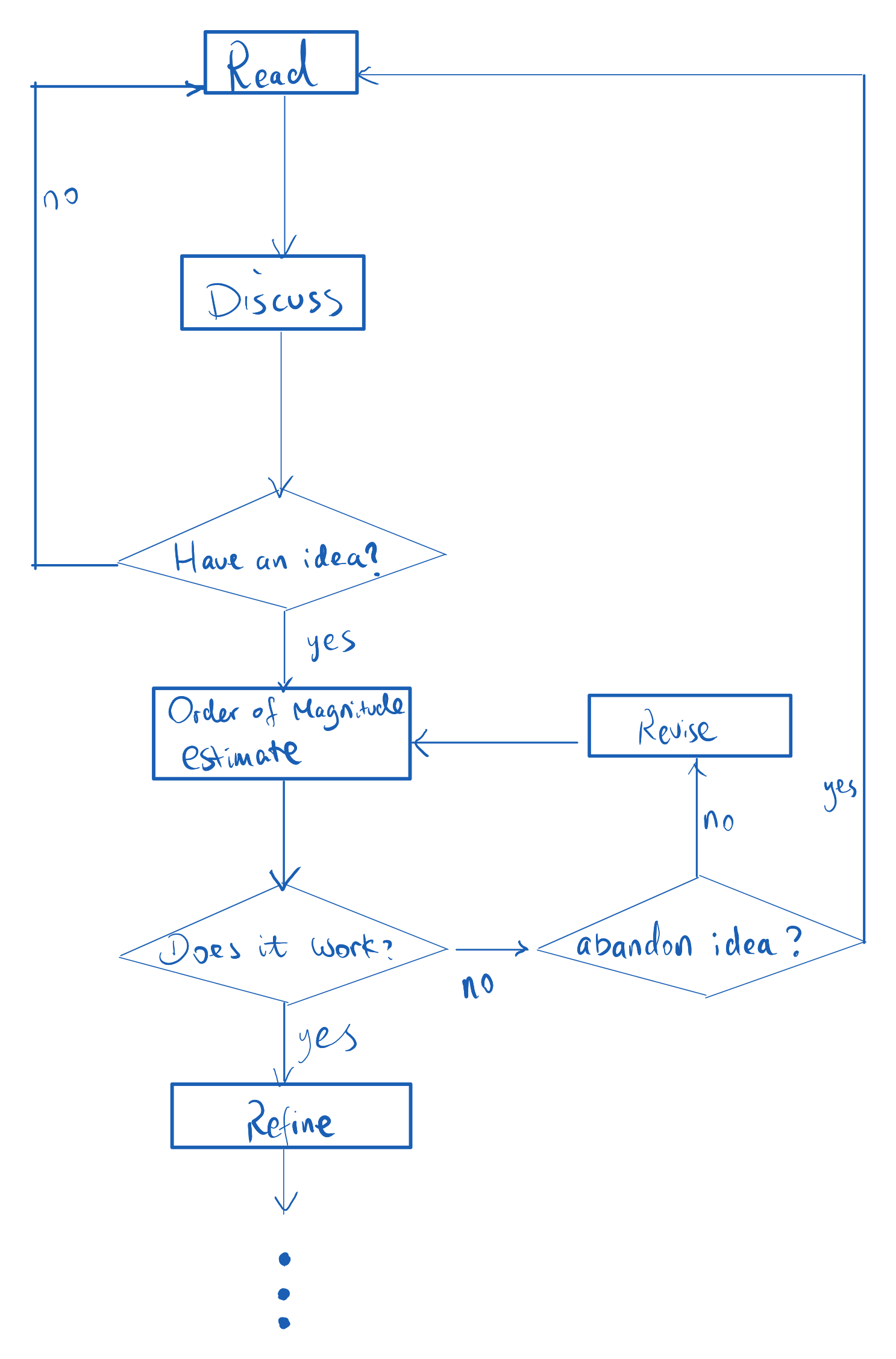

So how does it work? In a nutshell, in an order-of-magnitude estimate we lower the precision of the estimate to a certain degree by rounding the numbers to the closest decade, so 2≈1, 3≈1, 6≈10, etc. By intentionally lower the precision, in other words, coarse-graining, you no longer need to be accurate about getting everything that “right” in the first shot. This can drastically reduce the effort needed in the initial estimate, such as looking for the right numbers in the literature or computing them very accurately. If the results look interesting – meaning it indicates novel phenomena, or it disproves/falsifies some previously claimed results – you then go beyond the order-of-magnitude estimate and do a more serious one. Otherwise, you revise the model to a point it becomes interesting or you throw it away and think about something else. A flowchart for the early stage of any project roughly looks like this:

The caveat, though, is to keep in mind that

- the result will only hold within a couple of orders of magnitude, meaning if you get 30, it simply means it could be anywhere around 3 to 300, but it’s very unlikely to be 30,000,000;

- you are responsible for keeping track of the assumptions (either being aggressive or conservative,) and

- if the result looks promising, a more careful computation is in order.

Let’s look at a few examples.

What is the pressure of the tires in my Chevy Blazer?

It’s reasonable to assume the weight of an SUV is of the order of tons (one ton, a few tons, doesn’t matter for now.) Let’s denote it as \(\mathcal O(1)\) ton. Last time I checked my car still had four tires, each having about one palm’s contact area with the ground. Let’s give it an order of 10cm x 10cm, so \(\mathcal O(0.01) \rm m^2\). The tires are able to support my car, and we know that the pressure of the air is roughly isotropic, so the air pressure can be roughly estimated as

\begin{align} 1000 \, \mathrm{kg} \times 10 \, \mathrm{N}/\mathrm{kg} / \, 0.01 \mathrm{m}^2 /4 \, \mathrm{tires} \sim 2.5 \times 10^5 \, \mathrm{Pa}, \end{align}

where 1 Pascal is 1 N/m2. The atmosphere pressure near the surface of the Earth is at the order of 105 Pa, so very roughly every tire has about three times the atmospheric pressure (3 atm.) Note that this is an order-of-magnitude estimate, since my car could weigh more than a ton, and the contact area could be bigger or smaller, I should take the result as roughly saying 1-10 atmosphere. A Google search about the tire pressure gives me the recommended tire pressure “for SUV: 40 - 42 psi”. Converting the pound per square inch to atmosphere this is roughly 2.7 atm - 2.9 atm, not bad huh?

If it feels like the so-called “word problem” (or 应用题 in Chinese) to you, you are not wrong. Lots of the problems we physicists solve on a daily basis are just like that, perhaps with a bit more complications but qualitatively we are the word problem solvers. The fun part though is often times we are the ones that formulate the problem in words in the first place. Let’s look at another example.

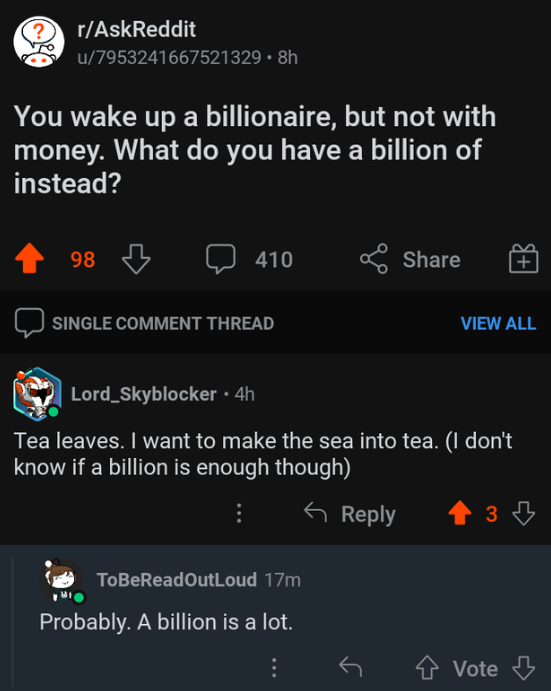

Can you turn the sea into tea if you pour a billion tea leaves into the sea?

I accidentally ran into this question on Reddit. I found it amusing so I did a bit of what we call “a quick estimate.”

Just for an order of magnitude estimate, the earth is covered with order one fraction of its surface in water. So the surface is roughly (1000km)2. Assuming the average ocean depth to be of the order of km, it’s 106 km3 water or 1018 litters. One billion tea leaves only get you one leaf per 109 litter water. It’s pretty dilute tea if you count that as tea at all.

See? It’s a lot like the “word problem” we solved during grade 1-5. You might think the above examples are not that useful in the real world. Let’s look at another real example that might help you win your next weekend’s trivia game.

Party king: how fast is the world’s fastest roller coaster? A. 15 mph, B. 150 mph, C. 300 mph

During a party game, my friend asked this question. Assuming the height of the roller coaster to be around 200 m, the terminal velocity by converting all the gravitational potential energy into kinetic energy gives me

\begin{align} \sqrt{2 g h} \sim \sqrt{2 \times 10\, m/s^2 \times 200 m } \sim 60 m/s \sim 140 mph. \end{align}

Not too far from B right? Googling it afterward, it seems the fastest one so far is Formula Rossa (149 mph), to be beaten by Falcon’s Flight (155+ mph) in 2023.

The order-of-magnitude estimate is something baked into almost every physicist’s natural (or not-so-natural) instinct. Next time you see there is a problem and someone’s first reaction is to grab a pen and a piece of paper and start doing some lousy-looking-but-really-useful estimate, s/he might be a physicist or at least has some good science/engineering background.

Jokes aside, it’s what I do when I sense real danger.

If a water reservoir breaks, how big an area can it damage?

Earlier in June, there was a flood warning in my hometown, where my parents still live. Knowing that there is a dam near my hometown, I was concerned about my family’s safety. Given the transparency of the local news channel (or rather the lack of it,) I did my own estimate.

The reservoir has a capacity of 1.4 billion m3. The distance between the reservoir and my hometown is about 30 km. If a release is ordered the water will be able to cover an area of 30 km by 30 km with a height of 1.5 meters. Of course, this doesn’t take into account the altitude or the local landscape but it still gave me some peace of mind knowing that my families are not in immediate danger.

Just to show you that the order-of-estimate finds its applications in physics, let us consider the last example.

How much dark matter can a neutron star capture NS, during its lifetime?

A neutron star is a very dense stellar object that has a size of ~\(\mathcal{O}(10)\)km with a mass of order \(\mathcal{O}(M_\odot)\). The gravitational waves emitted from mergers of neutron stars pairs give us some novel opportunities to have a peak of its composition as well as its structure (e.g. measuring its deformability.) On the other hand, dark matter is some 85% of the total matter in our Universe that we have only observed through evidence in the gravitational channel. Understanding their particle nature has been a hot topic that attracts lots of effort in the particle/astrophysics/cosmology communities. A question one can ask is how much dark matter can be found inside a neutron star, and whether it changes the neutron star merger signals.

Let’s do a very rough estimate. Since the neutron star is very dense, let’s assume that it sweeps through a space (filled with dark matter) with its geometric area. Assuming that every time it encounters a dark matter particle, the latter gets confined inside the neutron star. Admittedly, these are some aggressive assumptions. For starters, the actual neutron-dark matter interaction could be much weaker, leading to an effective sweeping area (or cross-section, in technical terms) much smaller than its geometric area. In addition, after one collision between dark matter and the neutron star, the dark matter particle is not guaranteed to lose enough energy to be trapped inside the neutron star. However, let us take the aggressive assumptions for now.

Let us take the age of the neutron star as 10 billion years (the age of the Universe being 13 billion years.) The relative speed between a neutron star and dark matter is roughly \(10^{-3}\) times the speed of light (~\(3\times 10^{8} \mathrm{m/s}\).) During the lifetime of the neutron star, the total area swept by the star is about

\begin{align} (10\,\mathrm{km})^2 \times 10^{10} \,\mathrm{years} \times 10^{-3}\, \mathrm{c} = 10^{38 }\,\mathrm{cm^3}. \end{align}

Dark matter’s density in our neighborhood is about \(0.4\,\mathrm{GeV/cm^3}\). Therefore, the amount of dark matter trapped inside the neutron star is

\begin{align} 0.4\,\mathrm{GeV/cm^3} \times 10^{38}\,\mathrm{cm^3} \approx 3 \times 10^{-20}\, \mathrm{M_{\odot}}. \end{align}

You can see that even with this aggressive assumption, the amount of dark matter captured by a neutron star can only make up a tiny fraction (roughly one part in 1020) of the neutron star mass.

Many people like the order-of-magnitude estimate for different reasons. For me, this converts the slow thinking process to the fast thinking process, if you are also a big fan of Daniel Kahneman.

In the end, here’s a word of warning: during an order-of-magnitude estimate, your intuition gets amplified, you get some quick answer, and it’s more fun, but that also means you could easily miss some important details. After all, this is just the first step of a serious estimate.

Edit as of 2022-12-29,Thu: Thanks to my colleague Dr. Nirmal Raj, it should be noted that the gravitational lensing effect can enhance the dark matter capturing by a few orders of magnitude. This is an example where order-of-magnitude estimate can make you jump too quick to conclusions neglecting certain details. However, even with five orders of magnitude enhancement, the captured mass fraction is still pretty tiny.

(Cover picture credit: here.)